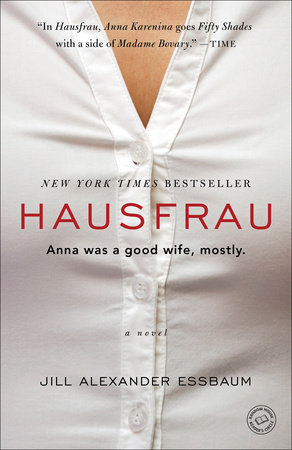

Hausfrau

A Novel

Jill Alexander Essbaum

Paperback

August 4, 2015 | ISBN 9780812987294

AmazonBarnes & NobleBooks A MillionBookshop.orgHudson BooksellersPowell'sTargetWalmart

Audiobook Download

March 17, 2015 | ISBN 9780553551594

Ebook

Bestseller

March 17, 2015 | ISBN 9780812997545

AmazonApple BooksBarnes & NobleBooks A MillionGoogle Play StoreKobo

About the Book

NEW YORK TIMES BESTSELLER • NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY SAN FRANCISCO CHRONICLE, THE HUFFINGTON POST, AND SHELF AWARENESS • “In Hausfrau, Anna Karenina goes Fifty Shades with a side of Madame Bovary.”—Time

“A debut novel about Anna, a bored housewife who, like her Tolstoyan namesake, throws herself into a psychosexual journey of self-discovery and tragedy.”—O: The Oprah Magazine

“Sexy and insightful, this gorgeously written novel opens a window into one woman’s desperate soul.”—People

Anna was a good wife, mostly. For readers of The Girl on the Train and The Woman Upstairs comes a striking debut novel of marriage, fidelity, sex, and morality, featuring a fascinating heroine who struggles to live a life with meaning.

Anna Benz, an American in her late thirties, lives with her Swiss husband, Bruno—a banker—and their three young children in a postcard-perfect suburb of Zürich. Though she leads a comfortable, well-appointed life, Anna is falling apart inside. Adrift and increasingly unable to connect with the emotionally unavailable Bruno or even with her own thoughts and feelings, Anna tries to rouse herself with new experiences: German language classes, Jungian analysis, and a series of sexual affairs she enters with an ease that surprises even her.

But Anna can’t easily extract herself from these affairs. When she wants to end them, she finds it’s difficult. Tensions escalate, and her lies start to spin out of control. Having crossed a moral threshold, Anna will discover where a woman goes when there is no going back.

Intimate, intense, and written with the precision of a Swiss Army knife, Jill Alexander Essbaum’s debut novel is an unforgettable story of marriage, fidelity, sex, morality, and most especially self. Navigating the lines between lust and love, guilt and shame, excuses and reasons, Anna Benz is an electrifying heroine whose passions and choices readers will debate with recognition and fury. Her story reveals, with honesty and great beauty, how we create ourselves and how we lose ourselves and the sometimes disastrous choices we make to find ourselves.

Praise for Hausfrau

“Elegant . . . There is much to admire in Essbaum’s intricately constructed, meticulously composed novel, including its virtuosic intercutting of past and present.”—Chicago Tribune

“For a first novelist, Essbaum is extraordinary because she is a poet. Her language is meticulous and resonant and daring.”—NPR’s Weekend Edition

“We’re in literary territory as familiar as Anna’s name, but Essbaum makes it fresh with sharp prose and psychological insight.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“This marvelously quiet book is psychologically complex and deeply intimate. . . . One of the smartest novels in recent memory.”—The Dallas Morning News

“Essbaum’s poignant, shocking debut novel rivets.”—Us Weekly

“A powerful, lyrical novel . . . Hausfrau boasts taut pacing and melodrama, but also a fully realized heroine as love-hateable as Emma Bovary.”—The Huffington Post

“Imagine Tom Perrotta’s American nowheresvilles swapped out for a tidy Zürich suburb, sprinkled liberally with sharp riffs on Swiss-German grammar and European hypocrisy.”—New York

“A debut novel about Anna, a bored housewife who, like her Tolstoyan namesake, throws herself into a psychosexual journey of self-discovery and tragedy.”—O: The Oprah Magazine

“Sexy and insightful, this gorgeously written novel opens a window into one woman’s desperate soul.”—People

Anna was a good wife, mostly. For readers of The Girl on the Train and The Woman Upstairs comes a striking debut novel of marriage, fidelity, sex, and morality, featuring a fascinating heroine who struggles to live a life with meaning.

Anna Benz, an American in her late thirties, lives with her Swiss husband, Bruno—a banker—and their three young children in a postcard-perfect suburb of Zürich. Though she leads a comfortable, well-appointed life, Anna is falling apart inside. Adrift and increasingly unable to connect with the emotionally unavailable Bruno or even with her own thoughts and feelings, Anna tries to rouse herself with new experiences: German language classes, Jungian analysis, and a series of sexual affairs she enters with an ease that surprises even her.

But Anna can’t easily extract herself from these affairs. When she wants to end them, she finds it’s difficult. Tensions escalate, and her lies start to spin out of control. Having crossed a moral threshold, Anna will discover where a woman goes when there is no going back.

Intimate, intense, and written with the precision of a Swiss Army knife, Jill Alexander Essbaum’s debut novel is an unforgettable story of marriage, fidelity, sex, morality, and most especially self. Navigating the lines between lust and love, guilt and shame, excuses and reasons, Anna Benz is an electrifying heroine whose passions and choices readers will debate with recognition and fury. Her story reveals, with honesty and great beauty, how we create ourselves and how we lose ourselves and the sometimes disastrous choices we make to find ourselves.

Praise for Hausfrau

“Elegant . . . There is much to admire in Essbaum’s intricately constructed, meticulously composed novel, including its virtuosic intercutting of past and present.”—Chicago Tribune

“For a first novelist, Essbaum is extraordinary because she is a poet. Her language is meticulous and resonant and daring.”—NPR’s Weekend Edition

“We’re in literary territory as familiar as Anna’s name, but Essbaum makes it fresh with sharp prose and psychological insight.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“This marvelously quiet book is psychologically complex and deeply intimate. . . . One of the smartest novels in recent memory.”—The Dallas Morning News

“Essbaum’s poignant, shocking debut novel rivets.”—Us Weekly

“A powerful, lyrical novel . . . Hausfrau boasts taut pacing and melodrama, but also a fully realized heroine as love-hateable as Emma Bovary.”—The Huffington Post

“Imagine Tom Perrotta’s American nowheresvilles swapped out for a tidy Zürich suburb, sprinkled liberally with sharp riffs on Swiss-German grammar and European hypocrisy.”—New York

Read more

Close